Nature – in the service of humans

Susse Georg

There are many ways of defining nature, but the view of nature as a resource has gradually become widespread. Here nature is regarded as a supplier of raw materials or resources, including the energy we use to maintain society. Among the essential raw materials are, for example, pure drinking water, agricultural land, rare earth metals and different types of energy carriers such as wood, coal and oil. Some of these materials are renewable, i.e. they can be restored (within the foreseeable future), while others can not and are considered non-renewable. Wood is considered renewable because a forest can grow again. On the other hand, coal, gas and oil – the fossil fuels, which are formed by organic matter (plants and algae) having been under pressure under the ground for many millions of years, are not considered renewable raw materials.

Humans use incredible amounts of raw materials. For this reason, there is great interest in determining the size of the stock of raw materials and how nature’s material flows function. In view of the increasing human population, determining whether there are enough resources to maintain our growing consumption so that future generations will also have an opportunity to use natural resources has become important. However, there is no simple answer to this question. Some have stressed that there are ‘limits to growth’, while others claim that as a result of technological development we will be able to find alternatives and, thereby, reduce or completely eliminate our dependence on certain limited raw materials. Although this may, of course, be possible in many cases, there seem to be some raw materials that can not be replaced by others. This includes, for example, phosphorous, which plays a crucial role in plant photosynthesis and in food production.

One can also apply a so-called process view of nature, where material and energy flows and their interaction with living organisms are central. This interaction between living organisms and their physical environment – between the biotic and the abiotic – takes place in ecosystems whose development is determined by the mutual influence and dependency of organisms and their environment. Thus, biological, physical and chemical processes form part of a wide range of mutually influencing cycles.

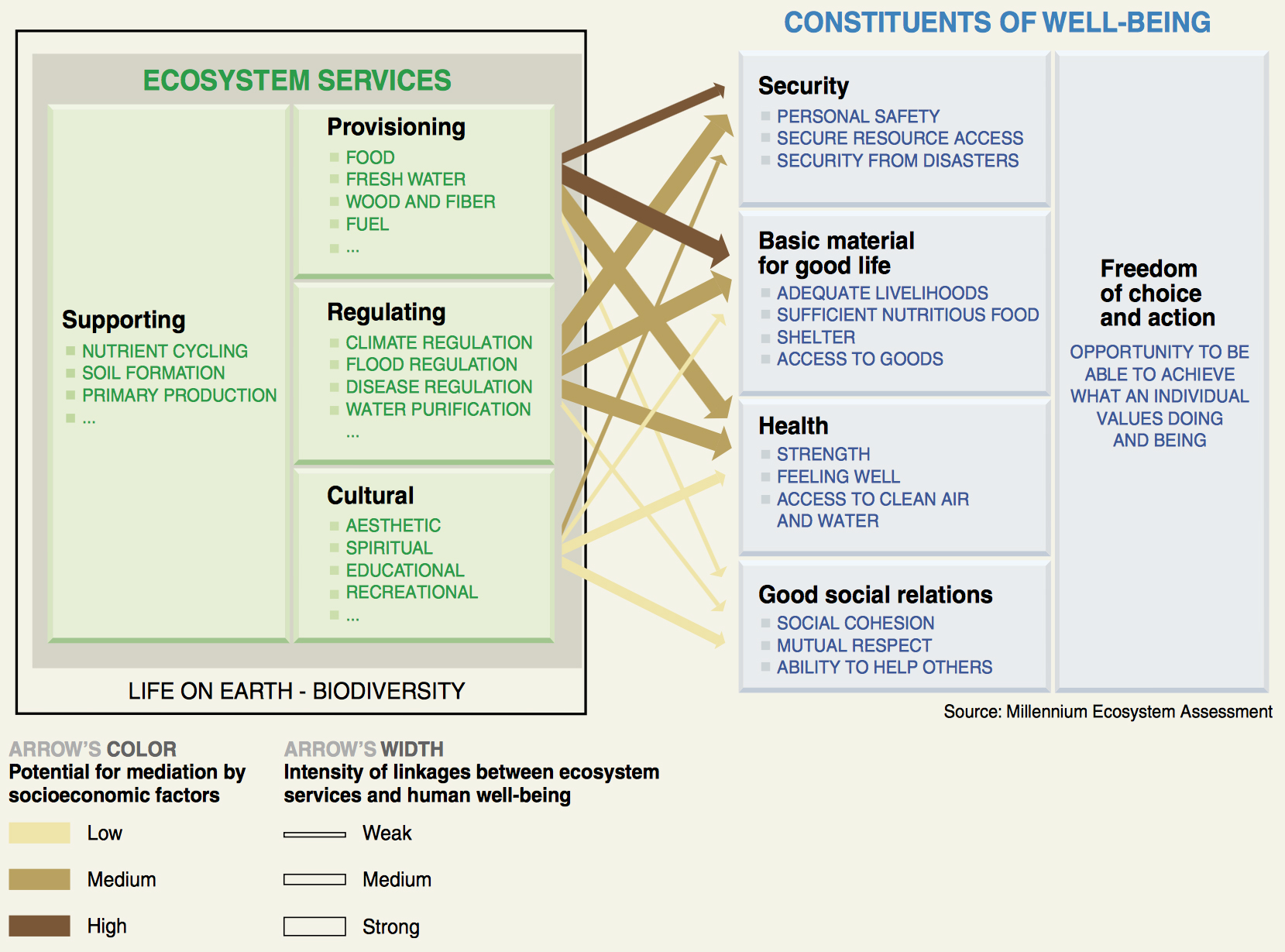

From a human perspective, the results of these processes are often termed ecosystem services, and they are vital to the maintenance of life. A distinction is made between the following four types of ecosystem services:

- Provisioning services such as the provision of food and wood for furniture production and construction. These services are not only based on natural resources and material/energy flows, but also depend on the use of human labour, machinery, etc.

- Regulatory services which are linked to the capacity of ecosystems to, for example, convert (and retain) nutrients in the soil or water and in this way may affect soil and water quality. The pollination of plants is another extremely important regulatory service as it affects food production. If plants were not pollinated, production would decrease. In this connection, the decline in the number of bees has attracted much attention.

- Cultural services are the experiences people can get from ecosystems, for example, in connection with recreational activities such as hiking in the woods, or picking flowers and berries. Landscapes can also provide such services by containing things that are considered valuable and worthy of conservation, for example, geological formations, such as cliffs, or different types of cultural heritage such as burial mounds.

- Supporting services are those that support the provision of the other services. Examples include photosynthesis, nutrient cycles and different soil conditions.

Therefore, ecosystem services are crucial to our well-being – our mutual relationships, health, quality of life and safety. For this reason, these services must be protected or managed in such a way that they are not destroyed by pollution or overuse. For example, chemicals can leach into the groundwater and destroy our drinking water, agricultural soils can be exhausted so that it is not possible to maintain agricultural production, and the habitat of pollinating insects can disappear so that the population of such insects decreases or completely disappears.

However, there are many indications that our use of ecosystem services is out of control. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report of 2005, during the last 50 years, ecosystems have changed so much that they are either overloaded or are about to be destroyed. In other words, humanity is well on the way to undermining society’s opportunities for future development as there is a risk of rapid irreversible changes to ecosystems which may have serious consequences for our well-being. Against this background, many have begun to assert that there are limits to what the planet’s ecosystems can cope with – the so-called planetary boundaries (see the infobox on ‘planetary boundaries’ in theme 3, ‘Growth and the environment’).

The two perspectives on human relationship with nature discussed above provide two different descriptions of the challenges we face. From a resource perspective, it is important to determine how many raw materials we have left, where they are and how accessible they are. What becomes worrying in this connection is whether we will run out of certain raw materials, and if so when, and whether it will be possible to find suitable alternatives and if not, what will be the social, political and economic consequences. In the process perspective, the focus is not on individual raw materials or resources, but rather the dynamic interaction between (biological) organisms and their surroundings and between different ecosystems. Thus, it represents a systemic perspective where the concern is not only that societal development will lead to resource scarcity, but also changes in the dynamics of ecosystems and, thus, their resilience. Limits to growth are also applicable here; limits connected to the destruction of the fragile balance of ecosystems, which, if pushed too far or destroyed, will undermine conditions for life. The transition of society in a more sustainable direction, thus, requires caution in terms of how we deal with nature regarding both our use of raw materials and ecosystem services.