Cities as transition arenas

Jens Stissing Jensen

Traditionally, energy, transport and water systems have primarily been analysed as nationally delimited systems, whereas, for example, cities or regions have been understood as local hubs that are subordinate to these national systems.

In recent years, however, an increasing number of studies have begun to regard societal systems as being more independent regional and urban phenomena. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, both Denmark and the rest of the world are characterised by increasing urbanisation. More and more people live in cities and, thus, use the city’s societal systems. Cities are, therefore, becoming increasingly central in the development of societal systems, and urban investments in system development and system transition are often significant.

Secondly, cities are often marked by problems and developmental processes that operate across individual societal systems. For example, developing urban areas requires coordinated planning of the connection between the urban practices and societal systems related to, for example, heat, energy, waste and mobility. Site-specific urban development processes often provide the opportunity to experiment with how different societal systems may be organised and integrated in new ways.

The development of Copenhagen’s harbour in recent decades is an example of how site-specific urban development can create transition processes by establishing new connections between urban systems and the way the city is used. This development began in the early 1980s, when the harbour was still organised around industrial production. The harbour, thus, housed a large number of industrial production companies, which used harbour waters both as a transport route and as a reservoir for toxic wastewater from production. In addition, the harbour was an integral part of the sewage system. During episodes of heavy rain, sewage was thus discharged into the harbour via a large number of drainage works to avoid flooding in the city when the capacity of the sewage network was exceeded.

However, from the early 1980s, industrial production began to move out of the harbour, and the harbour was left as an abandoned industrial area. The relocation of industrial production initiated a number of development activities in order to redefine the societal systems and urban activities in the harbour. From the beginning of the 1980s, the water in the harbour began to be defined as ‘biological water’ rather than ‘industrial water’ and the municipality began to measure its biological water quality. From the early 1990s, these biological measurements were translated into strategic aims for the biological quality of the harbour water. This put pressure on the wastewater system to reduce the overflow of sewage into the harbour.

Therefore, the municipality invested a significant amount to increase the capacity of the wastewater system. These investments led to new ideas about how the harbour could be used by the city’s citizens. These ideas involved the harbour as a natural area, which would offer the city’s residents an alternative to the absence of nature in the city. For example, one plan was to establish a so-called ‘harbour aquarium’ in the form of a glass tunnel at the bottom of the harbour, which would offer the townspeople the opportunity to experience the biological life of the harbour.

However, in the first years after the turn of the millennium, the vision of the natural harbour was replaced by the visions of ‘the city life harbour’ and the plan for a harbour aquarium was therefore never realised. However, the vision of the city life harbour already began in the early 1990s, when a long-term area development plan for the harbour was adopted by the municipality. One of the elements of the plan was to develop the recreational potential of the harbour. In the municipality, this led to a focus on ‘hygienic water quality’ rather than ‘biological water quality’, which became increasingly central during the 1990s and led to a further expansion of the wastewater infrastructure in order to reduce the overflow from the sewage system into the harbour. By 2002, the water quality had reached such a high level that direct contact with the water was rarely dangerous to people. Against this background, in 2002, a permanent harbour bathing area was successfully established at Islands Brygge and since then, several harbour baths have been opened and the wastewater system has been further developed in such a way that most of the harbour today is of hygienic bathing water quality.

The development of the ‘city life harbour’ thus links investments in the wastewater system with recreational urban activities, such as harbour bathing and diving and swimming competitions. This has received international attention and was highlighted, for example, when Copenhagen was named the European Environment Capital in 2014. The example shows that systems at the urban level are sometimes less path dependent than systems that are mainly organised and controlled by, for example, national actors. This is because urban systems, such as the sewage system, rarely have clearly defined borders or functions. In connection with the development of the harbour, the sewage system was thus assigned to new functions: Firstly as a supplier of biological water quality and since as a supplier of hygienic bathing water. Urban systems are, thus, typically more flexible than national systems because they are continuously adapted to diverse site-specific development processes.

Theories of sustainable transition

Jens Stissing Jensen

Over the last 15 years, political interest in a sustainable transition has created the foundation for the establishment of a new independent research field with an interest in how societal systems emerge and develop as well as how such systems may change. This research field takes as its point of departure the fact that societal systems typically have a tendency to maintain and expand the solutions and technologies that have historically been dominant. Experience thus shows that established societal systems have a tendency to result in ‘blindness’ or ‘hostility’ towards new technologies and solutions. One example is the dominance of the internal combustion engine within the modern transport system. In the early development of the modern transport system, this technology was far from dominant. For example, in American cities, electric vehicles played a central role in the early 20th century. The internal combustion engine did not become central until World War I when the technology was developed and standardised for military use. However, once the technology had become dominant as a result of the military development, it became predominant, and numerous attempts to develop and promote alternative technologies have since failed.

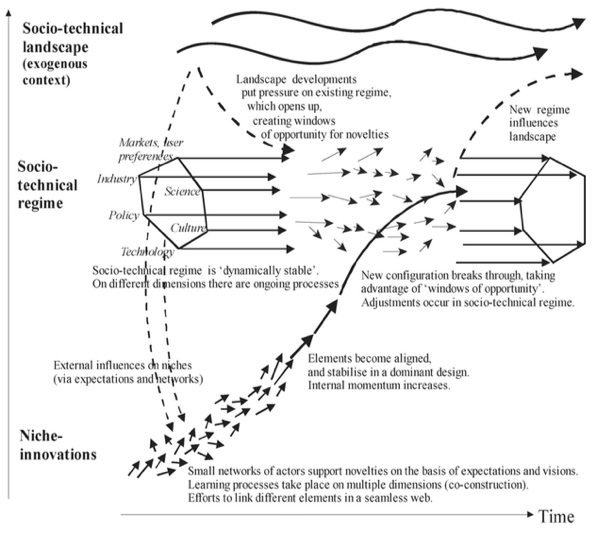

Niche, regime and landscape

In transition research, it has become common to divide the studies into the following three levels: niche, regime and landscape:

- Niche denotes a segment of a societal system where new development, which is often called innovation, is taking place. An example of a niche is organic farming, where an alternative form of production has been established within the wider societal agricultural system.

- Regime denotes the most widespread functional form of a societal system, which in the case of agriculture is represented by conventional pesticide-based agriculture.

- Finally, the landscape level represents an overall context for the societal system. At the level of landscape, there are, among others, cross-cutting economic structures, political trends and broader environmental circumstances. In relation to agriculture, the landscape level may include the general economic condition of agriculture, which is characterised by high debt and fierce competition, the efforts of certain interest organisations to promote a particular political agenda, and advancing climate change.

Selection

In the research literature, the tendency of societal systems to maintain and extend established technologies and solutions is typically explained using evolutionary systems logic. Within the social sciences, evolutionary systems logic was initially developed by innovation economists in the 1980s and 1990s.

Economists assumed that economic systems, like biological systems, evolve through evolutionary selection and variation processes. Like ecological systems that create diversity through mutations in connection with reproduction, economists assumed that economic systems constantly create new variations when companies and other entrepreneurs make new products, services, processes and business models. In order to explain which variations survive, become extinct or spread, economists also assumed that economic systems, like ecological systems, constitute so-called selective environments.

Analogous to the selective environment on the savannah or in the rainforest which consist of, for example, drought, cold, availability of food, diseases and predators, economists identified the key selection mechanisms in the selective environment of economic systems. They pointed out, for example, that physical infrastructure, technical standards, public regulation, industrial structures, the established knowledge-base of professions and the division of labour constitute selective mechanisms that are decisive in determining whether new variations survive and spread.

Based on this explanatory model, economists argued that only innovations that are competitive in relation to the overall system of selective mechanisms are viable within an economic system. This explained why established economic systems are typically hostile to radically new solutions because they often require that the selective mechanisms of the established economic system have a fundamentally different composition, for example new regulations, adaptation of the established infrastructure and completely new industrial standards. The evolutionary explanatory model, thus, described innovation as being ‘path-dependent’, in that only minor variations that are in line with the established selective mechanisms of the economic system survive and spread.

Transition research, thus, suggests that system transition involves cultivating variations through niche strategies and changing the selective environments of the societal system so that the system becomes more open to radical innovations. Research also indicates that transition can rarely be planned in the traditional sense because the development dynamics of the systems can rarely be controlled by a single actor or organisation.

Control

As described above, an established societal system consists of a wide range of different components (infrastructure, regulation, user practices, industrial division of labour), which have become woven together over time in a relatively rigid structure. These system structures constitute path-dependent selective environments that are, in general, hostile to radical innovations. At the same time, the various system components are rarely controlled by a single actor or organisation, which can initiate a coordinated transition of the system on the basis of long-term societal considerations. Is it at all possible to design, control or influence sustainable system transitions?

The dominant strategic idea about how the transition of established societal systems can be influenced focuses on supporting experimental niches that give radical innovation processes opportunities to develop relatively shielded from the normal selective environment of the societal system. This strategy involves cultivating technological or organisational variations that would otherwise not have been possible. In the transport system, advantageous tax rules and favourable parking for electric cars are examples of such protective strategies. The aim of these schemes is to support the development and spread of electric cars despite the various disadvantages of the electric car compared with traditional petrol and diesel cars, such as high production and development costs, a relatively short range and a lack of infrastructure for recharging batteries or changing battery.

This strategy has two components. The first component involves shielding new innovations from the selective environment of the established system, while the second involves using this shielded space to allow the new innovation to mature in the best way possible.

The previous literature on strategic niches identified public development programmes, in particular, as a tool to shield radical innovations from the selection mechanisms of established systems. However, historical studies indicate that radical innovations can rarely count on public development programmes ensuring the necessary long-term shielding so that they can mature and influence the overall societal system. This is due, among other things, to the fact that several different innovations typically compete for the limited resources that are available for supporting the development of a social system. For example, in the energy system, technologies such as wind power, solar cells, biogas and carbon capture and storage (CCS) are currently competing to define the direction of the transition.

Typically, shielding strategies are short-sighted, changeable and the subject of intense controversy. An illustrative example of this is documented in a study of the development of solar cell technology in Britain. In the 1970s, the technology was initially promoted by established energy companies as a large-scale technology, which secured a number of small state subsidy schemes for the technology, which were, however, quickly phased out. Thereafter, a number of research groups were successful in attracting further support for technology development through material research programmes. This research-oriented niche development was later replaced by a more practical application in work with developing countries where the technology was promoted in areas without central energy systems. Later, the technology was again introduced to the UK market - this time as an integrated building component in the construction industry. Then the technology was once again promoted as large-scale technology, which was to be organised in large solar farms. Recently, the technology has been promoted as a local and decentralised energy technology, i.e. as an alternative to the centralised energy system. The support schemes are, therefore, currently aimed at more decentralised systems. What this example illustrates is that new innovations rarely have the opportunity to develop in a linear and coherent process in stable niches. On the contrary, the development of radical innovations usually depends on political lobbying, which manages to ensure shielding from established selective environments for a limited time by identifying and cultivating applications that are favourable at specific times.

In addition to shielding radical innovations from the selective environment of the societal system, niche strategies also aim to organise the development and maturing of the radical innovation in the most efficient way. These activities involve, in particular, creating a connection between isolated experimental activities and ensuring that the innovation is not only developed in a single dimension. The development of wind turbines in Denmark is an example of successful niche development. While wind turbine technology was undergoing experimental development throughout most of the 20th century, its development only really gained momentum in the early 1980s. This was due to the fact that isolated experimental activities in the development of wind turbines were linked together through annual wind turbine conventions where mutual problems and experiences could be exchanged. These coordinated learning processes led, among others, to the establishment of a national wind turbine test centre. They also led to the development of new forms of ownership. Whereas in the early 1980s, wind turbines were typically owned by individuals, during the course of the 1980s, ownership became increasingly organised in windmill guilds. This ensured demand for ever larger, more expensive and more efficient turbines. This ownership model culminated in the establishment of the semi-circular wind turbine farm at Middelgrunden, just off the coast of Copenhagen in the mid-1990s. Subsequently, the construction and operation of wind turbines has increasingly been taken over by commercial energy companies, and production has been organised in international groups. However, the interest of the incumbent actors in wind turbines has been dependent on the niche-organised development that took place during the 1980s and 1990s. The example of wind turbines, therefore, illustrates how long-term niche activity may be necessary to ensure that a radical innovation is sufficiently developed to be accepted as relevant by actors who operate within the established selective environment of a societal system.

While the niche strategies are based on actors who typically play a marginal role within the established societal system, another strategic approach to system transition takes its point of departure in actors who already play a key role within an established societal system. The philosophy behind this strategy is to motivate these actors to gradually transform the existing selective environment in a more sustainable direction. This transformation may, for example, involve avoiding costly investment in infrastructure that is likely to lock the societal system into a particular pathway for many decades into the future. A key element of this strategy is to combine long-term, sustainable system visions with a so-called backcasting methodology (as opposed to forecasting, i.e. prediction which is based on current trends). The strategy is based on established system actors jointly developing a long-term sustainable system vision, which is typically radically different from the established system design. Then the vision is broken down through backcasting into short-term and less radical sub-goals, which can be handled by actors working within the framework of the normal selective environment of the established system.

Transition research, thus, asserts that system transitions involve both cultivating variations through niche strategies and modulating the established selective environment of the societal system so that the system becomes more open to radical innovations. Research also highlights that transitions can rarely be planned in the traditional sense because the development dynamics of the systems are rarely controlled by a single player or organisation.

Next: Cities as transition arenas

Introduction: Sustainable transitions

As the environmental consequences of increasing economic activities have become increasingly alarming, the need for a sustainable transition has also grown and become a more prominent theme in the public debate. Therefore, it is no longer uncommon to hear politicians and opinion formers talk about transforming our energy system, agriculture and transport into more sustainable alternatives such as wind and solar energy, organic farming, cycling and electric cars. In order to better understand and discuss such transition processes, it is useful to present some theoretical concepts that can clarify the problems. In this theme, therefore, we present some fundamental concepts and illustrative examples for understanding the sustainable transition of societal systems that can be applied to many different cases.

The term sustainable transition can cover several different areas, and one can talk about the sustainable transition of the whole of society’s economic metabolism or just the transition of certain societal systems. The term societal systems refers to systems such as the energy system, agriculture, transport and water supply. Such systems are also called socio-technical systems or provision systems, but in this theme we use the term societal systems. An important common feature of such systems is that they all have one or more overall aims. In the case of the energy system, for example, the aim is to produce and distribute energy to various areas such as house heating, industrial production, and the operation of vital infrastructure. A societal system is also characterised by being composed of many diverse interacting components and possessing a high degree of complexity. A societal system is, thus, a system that encompasses technologies, infrastructure, regulation, markets, end-user practices, and which is influenced by political, organisational and economic interests.

However, when discussing the sustainable transition of such systems, there is often a tendency to focus narrowly on the technological or market-related aspects of the system, which can lead to simplistic understanding and an unrealistic assessment of the opportunities for transition. Therefore, in this theme, we attempt to make the understanding of a sustainable transition a little more nuanced. This is based on the fact that a large number of production units and companies have limited opportunities to act independently because they operate within a framework of overriding societal systems. The transition perspective, thus, focuses on how individual companies and production units are often intertwined with social systems, which are typically difficult for the individual company or production unit to change. The transition perspective, thus, highlights that, in many cases, sustainability can not solely be achieved through the introduction of new technology at an individual plant or production unit. On the contrary, sustainability often requires that new technology is combined with ‘systemic’ (holistic) changes to regulation, infrastructure, markets and end-user practices that are connected with the overriding social systems.

Next: Theories of sustainable transition