Distribution of use values in a society

Inge Røpke

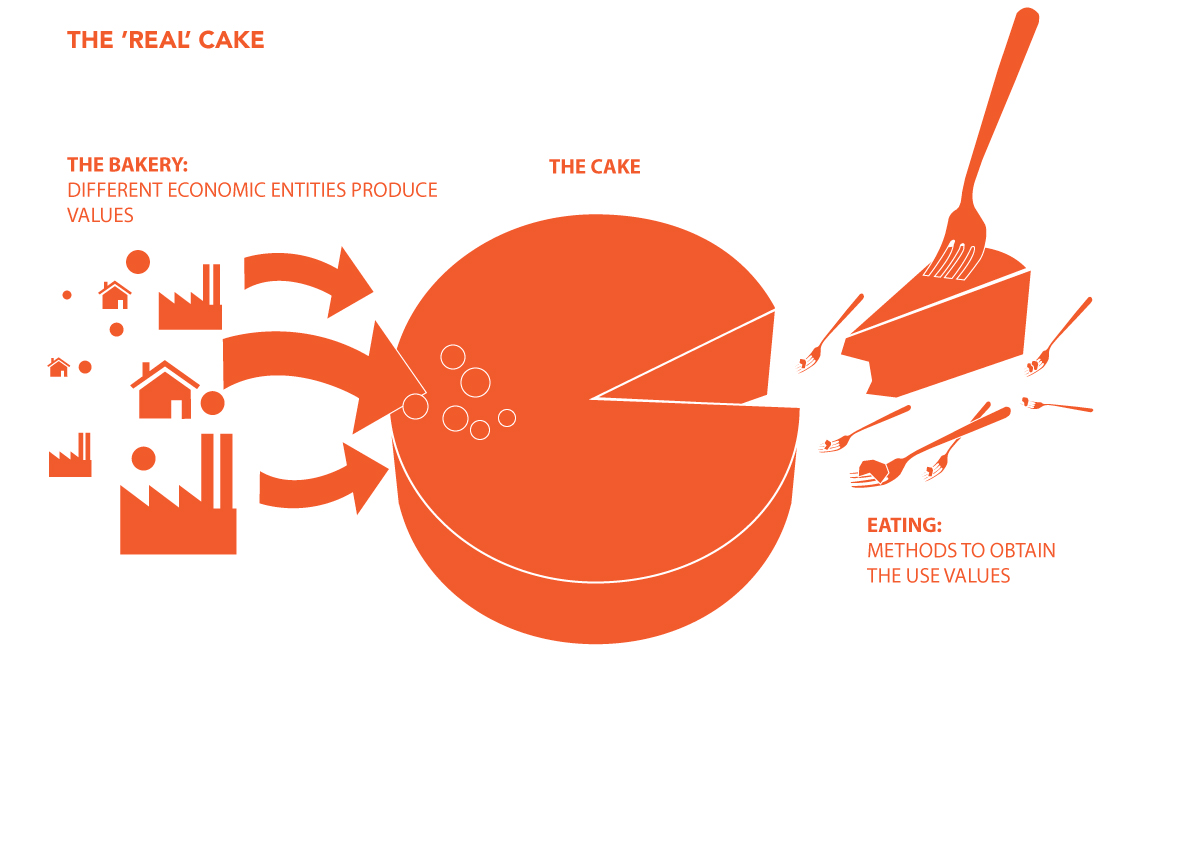

As previously mentioned in the theme on growth, ecological economics supports the idea that a society produces a ‘real cake’ during the course of a year, an amount of use values that society can either consume during the year or invest in future consumption opportunities. Even though the production result can not be measured in a meaningful way, we still have a clear idea that it will be unevenly distributed. Some groups in the society get better food, have larger homes, are more mobile, etc. than others. The distribution of goods is an aspect of the way society and the economic activities are organised.

Distribution is considered to be a political question, which mainstream economists will often seek to avoid by directing it to politicians. Many mainstream economists believe that their personal theories about how the economy works is value-free and can be used as a neutral basis for political debates. However, ecological economists consider this view to be totally misleading and instead emphasise that values are integrated in the concepts and perspectives one uses. In the field of ecological economics, distribution is clearly addressed: the recognition of biophysical limits is combined with a desire to redistribute to the benefit of the poor. Today we live in a world of great inequality and widespread poverty, and there is a great need to improve the living conditions of the most disadvantaged.

Biophysical limits imply that it is impossible to solve poverty problems solely through growth. Technological development may well make it possible to obtain more use value and higher living standards out of the resources, but this will still be insufficient. If this view of the situation is combined with a value-based belief that all people should be guaranteed good living standards, it results in an ethical demand to redistribute to the benefit of the poor.

Basic model for distribution

The traditional neoclassical circular flow model, where companies sell goods and services to households, which sell production factors to companies, encompasses the idea that production factors are paid in proportion to their contribution to production. The theory, thus, legitimises inequality as a result of anonymous market forces. In ecological economics, the basic model is different: there is no circular flow where everything fits together.

Instead, on the one hand, there is a production process where many different economic entities (companies, households, public institutions, local communities, organisations, etc.) help produce the production result - the real cake of use values - some of which are traded on markets. On the other hand, there is a distribution and consumption process, whereby members of society gain access to the use values by way of a number of methods. To continue with the cake metaphor, there is no general connection between individuals’ contribution to the bakery and their access to eat the cake. The allocation mechanisms are far more complex and are based on a long history of conflicts and power relationships that have crystallised into the current institutions and mechanisms.

Distribution mechanisms

The most decisive factor in terms of an individual’s access to use values is where they were born or possibly where they are living. Branco Milanovic, who is an expert in the study of distribution, calls it ‘citizenship rent’ - that an individual’s living standards depend more on where they are than what they do. You can be hard-working in a developing country and yet get very little out of it because your tools and society’s infrastructure are poor (as neoclassical economists would emphasise), and because local and global power structures put you in a weak position in the struggle for distribution. Personal effort is not the most decisive in terms of benefit.

It is obvious to divide a society’s allocation mechanisms into two broad groups depending on whether they are linked to markets or not. In markets, access to goods is determined by whether you have purchasing power in the form of money, while access in other contexts is decided by other types of institutions. For example, the distribution mechanisms within a household are usually based on conventions about who is entitled to what, to which there is a major element of care attached. With regards to the public sector, the distribution of goods is often based on rights. These may be rights to the transfer of purchasing power in the form of, for example, pensions or support for education, or they could be in the form of access to use goods, such as medical assistance or education, which are made available by the public sector.

As previously mentioned, purchasing power is crucial to be able to secure goods on markets. In modern societies, the vast majority depend on acquiring purchasing power. Some use value is created within households, for example, when we grow vegetables in the garden, make food, clean and look after the children. However, households also need a lot of goods and services that they can not produce themselves, while they have to acquire raw materials and equipment from other parts of the economy for their own production. How do they obtain purchasing power? In our society, most people would probably first think about working to gain purchasing power:

When we contribute to producing the real cake, we get a salary. Purchasing power can also be obtained by virtue of ownership of assets that are used in production such as land, buildings, machinery, patents, trademarks and other rights. The assets may be owned by individuals directly or indirectly through their ownership of, for example, shares in a company. Financing production through lending can also provide access to payment in the form of interest.

According to the neoclassical circular flow model, everything fits together: When companies sell goods, an amount is received which pays for the production factors in the form of salary, interest on loans, payment for the use of patents, stock dividends, etc. However, everything does not fit, partly because purchasing power also occurs in the form of capital gains. If a company is successful with its goods or if it owns an important patent, the price of its shares may increase. The owners can convert this into purchasing power through, for example, borrowing. Purchasing power can also arise in relation to the ownership of other assets as property rights sometimes provide a particularly high profit as a result of changes in society. For example, when railways were established, the land near the new stations increased in value. This form of earnings which is created by society is called ‘rent’ or ‘unearned income’ - a gain that the owner of the asset acquires solely through ownership and not by virtue of any effort. A more recent Danish example is the capital gains that many homeowners received as a result of the introduction of new types of loan in the early 2000s. Assets can also decrease in value, for example, land or houses losing value due to the construction of wind turbines or motorways nearby.

The allocation of purchasing power among society’s citizens, to a large extent, is based on the balance of power and associated institutions. The balance of power is decisive, not least for the relationship between what can be earned through work and ownership of assets, respectively. In societies with strong employee organisations, a relatively higher amount can be earned via paid employment than in societies with weak organisation. Historical conditions play a major role in the balance of power. For example, the large sacrifices made during WWII created the basis for strong ideological support to the construction of a welfare society for all, which was, amongst others, based on wealth taxes and a high rate of tax on high incomes. The establishment of the welfare state's social security system also put a limit on how hard workers could be pressurised. In many countries, this social compromise was actively attacked from the 1980s onwards, so the owners of assets became far stronger in the struggle over distribution. This has gradually manifested itself in the form of changed tax systems and a weaker social security safety net. In addition, privatisation has facilitated the establishment of private property rights for assets that had previously been communal or publicly owned. For example, this applies to different types of infrastructure and resources such as fish. Furthermore, the patenting of new areas, such as software and genetically- modified organisms, has been opened.

Purchasing power through credit

In modern societies, credit plays a major role in the distribution of purchasing power and the relationship between the flow of purchasing power and the real cake. In societies with well- developed banking systems, it is possible for companies and people with new ideas to start something without having the necessary purchasing power. Furthermore, they do not need to borrow purchasing power from others who would have to give up purchasing power because the banks (and the state) can create new purchasing power. In practice, it works as follows: the bank gives the company a loan of, for example, 1 million DKK, partly by preparing a loan document, which says that the company owes the bank 1 million DKK, which is subject to a certain rate of interest and which has to be paid back in a certain way; and partly by increasing the amount in the company’s bank account by 1 million DKK. The amount does not come from anywhere else; it is created as soon as the figure in the bank account is increased. The amount is now money, i.e. a commonly accepted means of payment. There is a limit to how much money a bank can create in this way, but there is a lot of scope for creating new purchasing power. The fact that money can be created through credit provides great opportunities for starting new production and, thus, increasing the real cake. At the same time, the process makes some new demands on the real cake. Firstly, the loan must be repaid plus interest. Secondly, the owners who may, for example, have contributed share capital, expect a return. The institutions of society can easily be arranged so that lenders and owners earn a return on their assets, which increases purchasing power more than the real cake increases as a result of the new initiative (if it was possible to measure the growth of the real cake).

The disparity between purchasing power and growth of the real cake is increased when banks create purchasing power, which they lend for the acquisition of existing assets such as housing. Trade in existing assets does not increase the real cake (although, in some cases, its usefulness), but the demands on the cake increase as the flow of purchasing power increases. The same occurs when the growth of society generates undeserved income in the form of capital gains. In addition, since the 1980s, the financial sector has developed increasingly complex mechanisms that increase the flow of purchasing power without contributing to the real cake. As a result, the total purchasing power demand on the real cake increases far more than the cake itself, and an increasing proportion of the demands are appropriated by the groups that are already best placed.

Increasing inequality is a problem in itself, especially in a world of biophysical limits. In addition, the imbalance contributes to the emergence of economic crises, while the financial mechanisms create bubbles with increasing asset prices as well as mountains of debt, which trigger financial crises.

The consequences of uneven distribution

Various institutions and mechanisms reinforce inequality once it has emerged. For example, the opportunity to inherit implies that new generations in rich families do not have to start from scratch, but instead enter the struggle over allocation with good cards in their hand. At the same time, large fortunes provide special opportunities to obtain higher interest rates and exploit tax havens, which companies in strong positions can utilise to become even stronger. In the United States, in particular, the question of whether significant inequality is undermining the political system because money has become so crucial for gaining political influence is being increasingly discussed.

The allocation mechanisms are sometimes defended by arguing that they help support technological development. For example, the patent system allows the initial outlay to be recouped after investing heavily in development. However, the system is being increasingly criticised for being too lucrative and, in some cases, a hindrance to development. More generally, it may make sense to introduce incentives that promote innovation, but the current structure of the allocation mechanisms leads to results that are completely out of proportion.

The desire to promote innovation is often linked to the idea that it increases the size of the real cake that is to be allocated. It is true that innovation can help increase the amount of use value derived from the resources, although this is not necessarily the case. In this regard, it is important to consider the more general point that both the direction of innovation and the composition of the cake are strongly influenced by the distribution of purchasing power. The cake is not baked first and then allocated afterwards. On the contrary, purchasing power determines what sort of cake is going to be baked.

[otw_shortcode_info_box border_type="bordered" border_style="bordered"]

Eflornithin and sleeping sickness

In this section, it is argued that the demand, based on the ability to pay, has an influence on the content of society’s cake. There follows an example of this from the textbook on ecological economics by Herman Daly and Joshua Farley.

Some decades ago, the pharmaceutical company, Aventis, developed a drug called Eflornithin, which could cure African sleeping sickness. There was high demand for the drug among poor Africans, but unfortunately they did not have enough purchasing power to ensure satisfactory income from the product as far as Aventis was concerned. Instead of marketing the product by focusing on curing African sleeping sickness, Aventis chose to sell the patent to another pharmaceutical company, which used Eflornithin as a drug to treat unwanted facial hair on women. This new product was in high demand among wealthy Westerners. This illustrates how purchasing power can be decisive in terms of which products end up on the market, thereby becoming a part of society’s cake.

However, this particular story ended well as the organisation, Médecins Sans Frontiers (Doctors Without Borders), threatened to publicise the issue, which forced Aventis to resume production of Eflornithin as a medicine against sleeping sickness for poor Africans.[/otw_shortcode_info_box]

Trade and globalisation

Inge Røpke

The idea that free trade is good can be seen as one of the ideas that support the growth engine. However, the idea is challenged when adopting an ecological economics perspective. This section gives an example of how a different picture emerges when looking through biophysical glasses than when wearing more traditional economy glasses.

It is widely accepted that free trade is good. The most important argument is that trade provides greater potential for the division of labour and specialisation, which means that overall production will increase because resources are used in the most efficient manner. Each country can specialise in the industries for which they are best equipped and through trade gain access to a greater amount of goods than the country could have produced in isolation. The obstruction of access to larger markets by barriers may be problematic, especially in small countries because the national market may be too small to exploit economies of scale. Furthermore, an argument for free trade is that everyone is exposed to competition, which means they are forced to increase productivity.

The idea of free trade as being good for everyone has been thoroughly criticised, also from other perspectives than the biophysical. For example, the idea can be criticised for adopting a static perspective by emphasising the benefits that are connected to the division of labour and specialisation at a given point in time. In contrast, a dynamic perspective would emphasise the importance of trade for the development of a country over time. In order to complete the transition from an agricultural to industrial society, it is obviously essential to build industry. However, this may be difficult if the process is not protected from competition from more advanced countries. If predominantly raw material-producing countries are forced into free trade, they run the risk of ending up in a specialisation trap, which may be difficult to escape. Therefore, it is no surprise that the vast majority of countries that have successfully undergone industrialisation have managed to do so through protection against foreign competition. As industry becomes stronger, the country can gradually be exposed to competition, thereby increasing the pressure for efficiency. What may also be crucial for a successful industrialisation process is the regulation of the composition of imports by the state so that, for example, machines for industry receive higher priority than consumer goods, which is what Denmark did after World War II.

The process can be made difficult in many ways. For example, the industrialised countries have used a form of asymmetric trade liberalisation by refraining from imposing duties on imports of raw materials, such as cotton from developing countries, while imposing high duties or quantitative restrictions on imports of finished goods such as cotton clothing from the same countries, which therefore found it more difficult to industrialise. As another example, the EU’s state aid for its agricultural production and exports has made it difficult for some developing countries to develop their agricultural sector. At the same time, local elites in some developing countries have prioritised making themselves rich through raw material exports instead of investing in economic development.

In recent decades, some developing countries have managed to industrialise and use trade as a tool in the process. One often hears the argument that trade and globalisation have contributed to lifting 300 million Chinese people out of poverty. It is true that regulated trade (not free trade) has been an important part of industrialisation, not least in China, which needed to import advanced technology from other countries and obtained the necessary funds for the imports through the export of labour-intensive industrial goods (textiles, assembly of electronics, household utensils, tools, toys). However, from a biophysical perspective, the fact that the development process involved the population of the rich countries increasing their material consumption is problematic. Due to the very low wages in the newly-industrialised countries, many products became very cheap, which helped to promote the throw-away culture in the rich countries and that a given amount of money could mobilise a larger amount of material resources. Furthermore, in the case of many products, this meant that production resulted in more pollution because Chinese energy production was based on coal from less efficient power plants. The point of this perspective is not to argue that China and other countries should not industrialise and lift their population out of poverty, but to illustrate the absurdity that the present system only allows the process by making the rich richer and by undermining the environment. A more environmentally rational and more ethically defensible system would lift people out of poverty without increasing the consumption of those who already have so much.

The biophysical perspective includes other criticisms. For example, it is obvious to focus on the environmental aspects of transport. The strong growth in global trade is based, amongst others, on low and declining transport costs because of major efficiency improvements, especially in the form of labour-saving technology. Even though the energy consumption per transported unit has also fallen, energy consumption and pollution that result from freight transport are significant - costs which are not paid for. If the environmental costs of transportation had to be paid for, it would not be worth engaging in trade to the same extent as now. Global trade flows also hamper the circular economy for biomass. For example, exporting soy from Latin America to feed pigs in Denmark, which results in nutrients ending up in Danish watercourses, is not very rational.

Ecological economics also highlights the problematic fact that trade helps to conceal biophysical limits. On the one hand, that countries complement each other in a biophysical sense may be seen as a great advantage. When economic growth in a country encounters biophysical limits, such as a lack of soil, water, forest, minerals, energy - trade makes it possible to overcome the barriers and continue growth. On the other hand, this process means that all resources are exploited to the utmost, and that humanity approaches many biophysical limits at once. The potential to bypass the limits means that we are oblivious to the danger signals that could have served as a feedback mechanism making us change course.

So far, the discussion on trade has implied that it takes place between countries, but most trade actually occurs between companies. Nation states can regulate the framework, but today many companies are so large that they have significant influence on the framework and can play states against each other. The theory that trade is beneficial to all the countries involved is based on the assumption that production factors, such as work and capital, are tied to particular countries in the same way as raw materials. However, the increasing liberalisation of, in particular, international capital flows since the 1980s has meant that this assumption is being met less and less frequently. The large multi-national companies organise supply chains throughout the world and exploit the benefits that are associated with specific locations, and organise capital transfers in order to minimise their tax payments. Globalisation, to a great extent, challenges states’ ability to regulate product standards and environmental conditions, while undermining unions’ ability to defend labour and working conditions. In addition, companies are trying to privatise an ever- increasing number of areas, so money can be made from, for example, water supply, education and health services, which are or have been organised collectively in many countries. Current discussions on trade agreements only concern the reduction of tariffs and the elimination of quantitative restrictions to a limited extent. They are more concerned with expanding the scope of the transnational corporations, making more areas subject to privatisation, preventing states from tightening product and environmental regulation and securing earnings on intellectual property rights.

Even though the old free trade argument has been undermined by the mobility of capital, liberalists still assert that free trade is beneficial to everyone because it results in goods being as cheap as possible: they are produced where the costs are lowest, while competition constantly ensures that productivity increases by as much as possible. Whether this is actually the case in practice may be questioned, but what is more important is that high costs are excluded from the calculation: the environment suffers damage, working conditions are undermined, and the welfare states can not be financed. For the individual, that it is possible to fly cheaply with low-cost airlines may seem like a gain, but the collective costs include climate destruction, deteriorating working conditions and the dismantling of the welfare state.

The effects on distribution are complex. On the one hand, that income has risen for large groups in poor countries may be considered progress, but on the other hand, globalisation has increased inequality in many industrialised countries, especially in the United States and the UK, where the wealthiest have become richer, while the middle-class have lost ground. The fact that there have not been many protests for a long time is probably due to the combination of low prices for many product groups and the significant growth in credit, which has made it possible to maintain living standards - until the financial crisis put an end to that.

In the longer term, an ecological economics approach would suggest that the economies be more self-sustaining in the biophysical sense, so that the cycles can be more easily closed, transport reduced and the constraints made more visible. In many areas, demographic and technological development has made trade unavoidable - in some areas, enough food can only be obtained in this way, while in Denmark, for example, it is hard to imagine an economy without electronic equipment, for which we do not have the resources to manufacture. However, regulation of the environment, working conditions, capital flows and much more is necessary to ensure that trade occurs on reasonable terms and that we do not get the goods too cheaply.

Next: Distribution of use values in a society

The growth engine

Inge Røpke

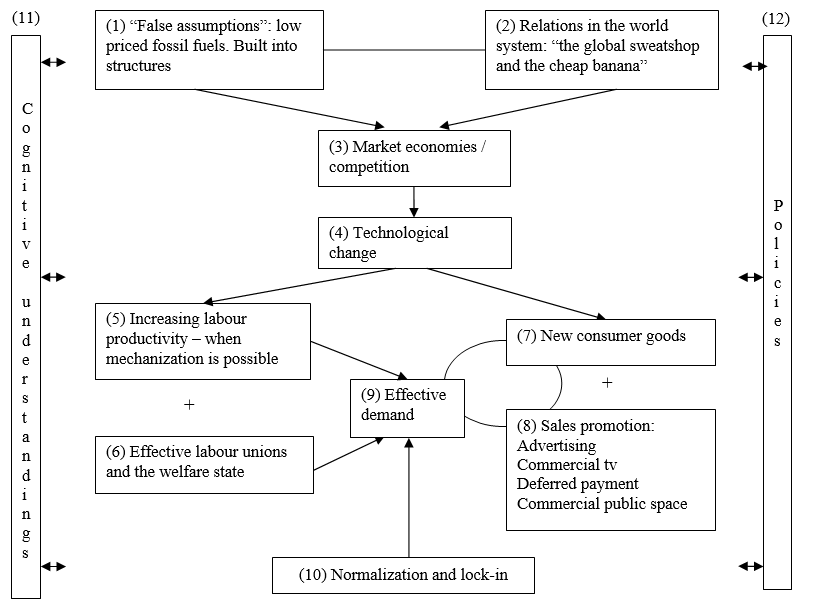

Since the start of industrialisation and especially during the post-WW2 period, we who live in the rich countries have been able to increase our material consumption significantly. In the figure below, some of the key mechanisms behind the growing consumption are outlined. In the accompanying explanation, the numbers in brackets refer to the boxes in the figure. This section illustrates how the unequal distribution itself contributes to growth of the metabolism.

The basic prerequisites for growth in consumption

The basic prerequisites for growth in consumption

There are two basic prerequisites for the strong growth of living standards in the rich part of the world. First, the significant growth in consumption since the start of industrialisation would have been impossible without access to cheap fossil fuels (1). Fossil fuels equip us with many ‘energy slaves’ that are used to mechanise production processes and allow large increases in labour productivity, i.e. in the production of goods per work hour. Until recently, fuels have, in general, been relatively cheap because extracting them has been cheap - but prices have also fluctuated and have been heavily influenced by particular political conditions. In contrast, prices only reflect the long-range of environmental and social costs caused by the extraction and use of fossil fuels to a very limited extent. Such costs include mining accidents, oil spills, acidification, particle pollution and global warming. As these costs are not reflected in the price, economic growth can be said to be based on ‘false assumptions’, and after more than one-hundred-and-fifty years with these assumptions, they have been built into the social and physical structures of society, such as the development of private car ownership and the associated road systems, suburban developments and shopping centres based on low petrol prices.

The second basic prerequisite for high consumption is linked to international relations and the balance of power between the countries in the world system as the early industrialised countries achieved a power position that made it possible to procure raw materials and exploit cheap labour in other parts of the world (2). As industrialisation developed, international relations were already marked by the European countries’ colonisation of other parts of the world, and industrialisation reinforced the need to collect raw materials in the colonies. For example, England obtained cotton from India for the development of its textile industry, while India’s textile production was undermined by trade restrictions. Not least with the help of protectionism, a number of European countries, the United States and Japan managed to catch up with England, which had been leading in terms of industrialisation, while the colonies were kept as commodity suppliers. Despite decolonisation after World War II, raw material exports still play a major role in many countries, partly because many mechanisms in the global trade and capital transfer systems make it difficult to break the patterns. A certain amount of industrialisation in connection with the relocation of activities from rich to poor countries has occurred, and the global production chains ensure cheap goods from work in the global sweatshop. In addition, political interventions support access to raw materials and agricultural goods in slightly more elegant ways than the military coup in Guatemala, which, as described by the ecological economist, Juliet Schor, secured the ‘cheap banana’ in 1954. However, as discussed in the section on trade and globalisation below, some countries, such as South Korea and China, have successfully established an internal industrial dynamic and changed the country’s position in the world system.

The global balance of power has made it possible to obtain cheap raw materials from mines, forests and agricultural land in poor countries, and gradually the low-paid labour has also delivered industrial products such as textiles, electronics, toys, etc. at very low prices. In biophysical terms, the massive growth in international trade since the Second World War has contributed to the fact that the population in rich countries have been able to increase their material living standards very significantly: the low prices mean that a lot of material resources can be bought for the money. Even in the poor countries, some groups have become richer, but in many places, trade union organisations and social systems are weak or non-existent, so there are large groups that do not receive much of the results. In addition, the environmental costs are enormous including pollution, deforestation, the impoverishment of soil and water resources, while in many areas, native populations have been crushed as resources are extracted in increasingly remote areas. In the field of ecological economics and political ecology, a key research field involves highlighting the environmental conflicts that arise as a result of the extraction and processing of raw materials and the disposal of waste.

[otw_shortcode_info_box border_type="bordered" border_style="bordered"]Environmental conflicts

The unequal global balance of power and the activities of large companies around the globe often give rise to so-called environmental conflicts, where local populations and other activists fight against an environmentally harmful activity of a company or state. The term ‘commodity frontiers’ is used to denote the hot spots where such environmental conflicts arise. Commodity frontiers, thus, refer to the places in the world where the extraction and processing of raw materials and waste disposal take place.

In a major international research project called EJOLT (Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade), researchers and activists, for a number of years, have mapped and described environmental conflicts worldwide in an interactive atlas called the Environmental Justice Atlas (see http://ejatlas.org/). The aim of the atlas is to give a voice to groups who are struggling for environmental justice and to focus on endangered local communities, which are often powerless against multinational companies and national politics and are rarely represented in the media. Furthermore, the project’s goal is to draw attention to the negative consequences of the privatisation of natural resources such as water.

The atlas provides several opportunities for locating and investigating environmental conflicts around the world. It is possible to search for conflicts that involve a particular resource (water or gold, for example) or for conflicts involving a particular company (e.g. Shell).

One of the conclusions of the project is that the adverse consequences of the extraction and processing of raw materials and the disposal of waste are unfairly distributed and most often affect the poor, women, minorities and, in particular, indigenous peoples.[/otw_shortcode_info_box]

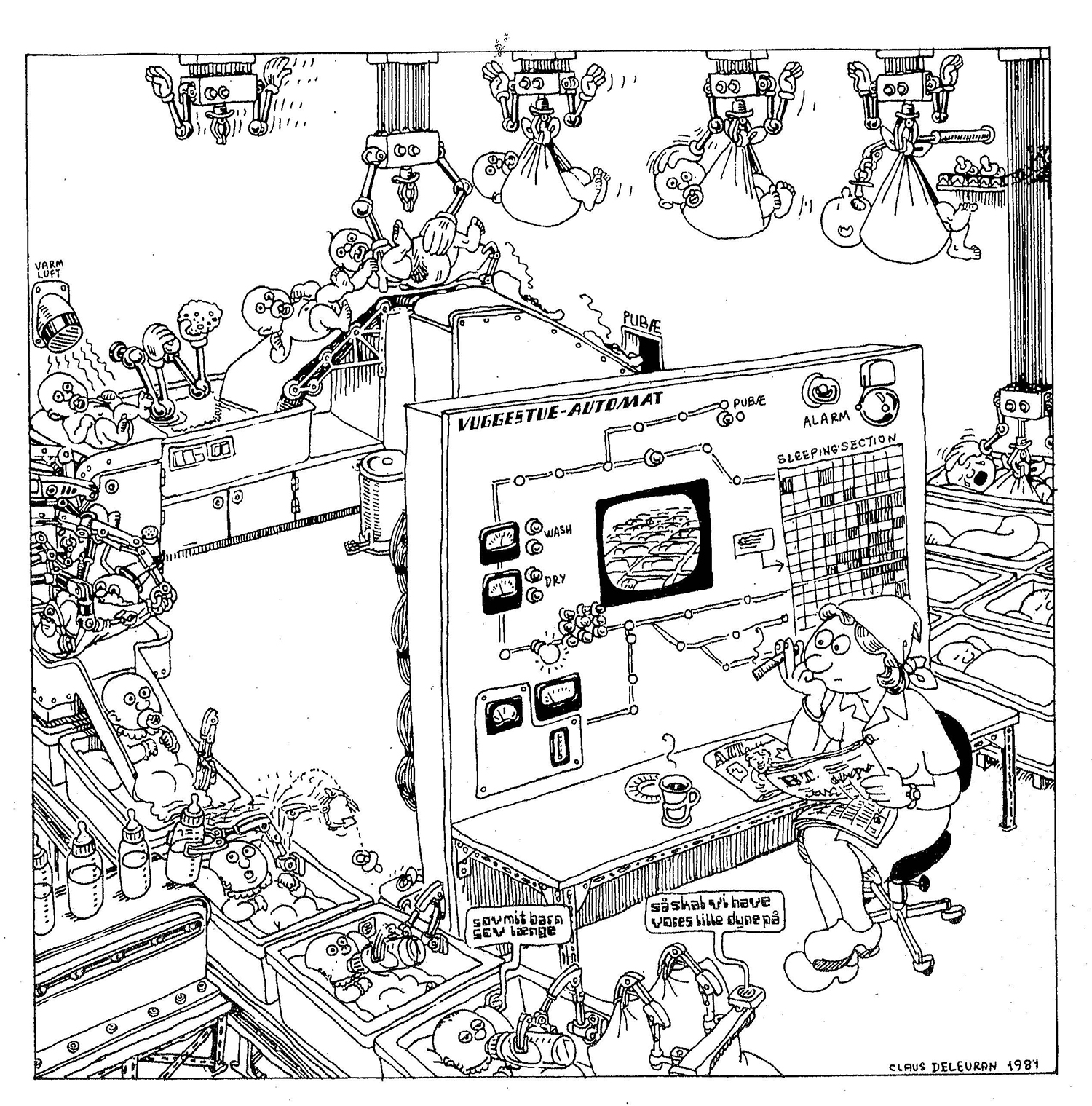

The driving forces behind consumption growth

The basic preconditions for high consumption - cheap fossil fuels and access to other cheap resources and labour - are complemented by a strong engine: market economy competition (3). A capitalistic market economy is based on competition between the producers, who must constantly strive to develop technological and organisational innovations (4). If a company’s activities are insufficiently profitable, it will not be able to attract capital and ensure its long-term survival, and renewal is crucial to profitability. The innovations partly aim at reducing costs, and partly at offering consumers new and tempting goods and services. When energy is cheap, efforts to reduce costs will be concentrated on increasing labour productivity through mechanisation and automation, where energy in combination with machines replaces labour (5). This focus is enhanced when employees succeed in obtaining higher wages and greater social security through the formation of trade unions and the establishment of a social security net in the welfare state (6). Such strength positions enable employees to get a share in the yield of increased labour productivity and achieve an ever higher standard of living - a process that encourages a continued focus on increasing labour productivity. However, not all production processes are easy to mechanise: It is difficult to provide certain labour-intensive services such as care, repair, hair cutting and theatre performances more effectively through the use of fossil fuels, so they tend to become increasingly expensive compared to material goods. In this way, consumers are motivated to buy more material goods rather than ‘sacrificing’ still more of these in order to purchase labour- intensive services.

When employees succeed in gaining higher wages, a market for the products that are produced by the companies emerges and consumer demand is stimulated by the supply of new consumer goods, new variants of known goods (7) and various forms of promotion such as advertisements and hire purchase systems (8). Everyday life becomes increasingly embedded in commercial offers as both television and public spaces display the many tempting opportunities. With the exception of the periodic crises, the supply and demand of consumer goods, thus, reinforce each other: Increasing wages ensure customers’ ability to purchase the products (9). The mutually reinforcing circle of supply and demand, productivity growth and rising standards of living constitute a growth engine that enlarges the biophysical metabolism over time. However, supply and demand are not always in balance at the macro-level - demand may be insufficient; the profitable investment opportunities too limited; bubbles in the financial sector may affect the real economy - so in periods, growth is interrupted by economic crises involving bankruptcies and unemployment.

Maintaining consumption growth: normalisation and lock-in

Most people in the Global North willingly play their role as consumers in the growth engine and do not consider themselves to be particularly extravagant. This is due, among other things, to the processes linked to normalisation and lock-in (10). When there is an economic boom, there is often a craze for a particular type of consumer good, as illustrated, for example, by the wave of housing improvements (first kitchens and then bathrooms) that were made up to the financial crisis or the purchase of flat screens in the 2000s. When the boom is in progress, improvements may seem extravagant and feel like pampering, but as time passes, the new standards become normalised: Having more than one bathroom in the home and flat screens in several rooms will become the new norm and will be expected. Some normalisation processes involve changes on several levels, such as changes in social discourses, political measures, institutional renewal, construction of infrastructure and new scientific insights. The story of the spread of air conditioning in a number of countries is an interesting example of a normalisation process that involves all these aspects, and currently, the integration of information and communication technologies in everyday life provides an opportunity to study such processes in full development.

When new products and a higher standard of living become normalised, the new standards are built into society’s social and material structures and can, thus, develop into a form of constraint. In a car-based society with vast suburbs and an inadequately developed collective transport system, the car becomes a necessity, or at least a good that is difficult to do without. In this way, the other side of the coin of freedom is constraint. When there are no longer any local stores, you have to shop in the supermarket and when houses are built to include air conditioning, they can be uninhabitable without, and when music can no longer be purchased on vinyl, the music lover must start to buy the new media. In addition to material constraints and incentives, various institutional factors can also help maintain living standards and consumption patterns. For example, car transport is encouraged by regulatory institutions such as transport allowance and the demand that unemployed people must accept job offers from employers located far from their homes. Normative and cognitive institutions, such as the perception that passing a driving test is a ritual step on the way to adulthood and the tendency to associate the car with personal freedom, have a similar influence.

In general, social and material inflexibility can help to bind consumers to resource-intensive lifestyles. For example, the labour market institutions in many countries are calling for full-time employment because the rules make it more expensive for employers to have a large number of employees sharing a set number of work hours. When the system encourages employees to choose income instead of leisure time, it initiates a process that Schor has termed a ‘work-and- spend cycle’ - a cycle that is also stimulated by the busyness of modern families and the development of shopping as a popular recreational activity.

The ideological and political framework for consumption growth

The engine of consumption growth functions within a supporting framework of cognitive understandings and policies. The cognitive understandings (11) include the idea of economic growth as an absolute good, regardless of the standard of living a society has already achieved. There are many other ideas such as: welfare is directly linked to income; economic growth in the rich countries has a positive effect in poor countries through the demand for their products; free trade is good for all parties involved; markets and healthy competition contribute to the common good; technological change is synonymous with social progress; and environmental problems can be solved with more efficient technologies. These ideas are controversial, but they are still dominant and are reflected in different policies (12), such as the promotion of free trade (although at times excluding trade restrictions, which are beneficial to the rich countries) and competitiveness, the privatisation and liberalisation of markets, the implementation of consumer policies that focus on ensuring low prices, the construction of more and more highways and the continuance of low energy prices.

Introduction: Driving forces and distribution

In the theme on the relationship between growth and the environment, it is argued that there are environmental limits to growth in living standards. But what drives growth and how growth is distributed is not addressed. In this theme, the focus is on the driving forces behind economic growth and the relationship between growth and distribution. Distribution is about who benefits from the growth and there are two aspects to this. Firstly, inequality in itself is one of the driving forces behind the fact that in the rich countries we have been able to increase our material consumption by so much. Secondly, limits to growth mean that there is an ethical responsibility to share.