Markets and environmental regulation

Susse Georg & Inge Røpke

There is no direct connection between the way in which property rights for resources are organised and the way in which the products that are produced based on the resources reach consumers in the end. The products can reach the consumers in several ways. Firstly, producers can use the products themselves, which is what households often do when they grow their own vegetables or keep chickens in the garden, while fishermen can eat the fish they have caught. Secondly, products may be given away, such as between friends, or as often happens between the public authorities and citizens. Thirdly, the products may be distributed among consumers through markets. Markets can distribute goods that are made within the framework of different property rights systems and by different economic entities (households, companies, public authorities). This means, for example, that the ownership and use of a resource may be organised as a commons, while the products of resource use can be traded on a market. As markets in modern societies play an important role as a link in delivering the products to consumers, it is worth examining how they function and the role they can play in environmental regulation.

[otw_shortcode_info_box border_type="bordered" border_style="bordered"]Free markets do not exist

In the debate about markets and the environment, a contrast is often made between free markets and regulation, where regulation is considered to be something that impedes the functioning of the free market. However, within ecological economics, this is considered to be a false opposition. As described in the sections on conflicts of interest and side-effects, environmental regulation may indeed imply restrictions on what the individual owner of a resource may do with his property because the interests of others or ‘the common good’ have to be taken into account. But this constitutes only a very small part of all the regulations that make up the conditions for a market. There is simply no such thing as a free market. As the development economist, Ha-Joon Chang, puts it (see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4BelDrWWt0), all markets are regulated: If you think a particular market is free, it is only because you agree so much with the regulations that support the market that you can not see them. For example, few would advocate reinstating child labour. The former US Labour Minister and political scientist, Robert Reich, makes a similar point here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dikqwpp3ylA (myth No. 2). In an environmental perspective, what is important is regulating and designing markets in ways that promote environmental goals.[/otw_shortcode_info_box]

A market is often described as a place where trade occurs. It is a place where sellers and buyers meet. In return for payment, buyers receive some of the sellers’ goods. Think of flower and fruit markets or flea markets: the buyer and seller are in close interaction, but this relationship becomes more distant in a supermarket. You are not in direct contact with the seller. There are other markets where this relationship is even less clear: Just think of the electricity market, the market for CO2 quotas or the financial market. Here the distance between the buyer and the seller is very great, and the relationship between them very indirect. In order to maintain a market, there must be some buyers who keep returning. However, it is primarily the sellers who determine how stable markets are because it is they who decide what is sold and at what price. Although there is a certain degree of reciprocity between buyers and sellers, it is the sellers’ interest to survive - to ensure a reasonable income (profit). The opportunities for this are influenced by who else is selling goods on the market – the competitors - and what they are doing.

Even though the above markets are very different in terms of the products and the type of buyers and sellers, they are all characterised by specific rules. The economic sociologist, Neil Fligstein, identifies three types of rule, which together characterise all markets. These are rules that specify: (1) property rights; (2) control or governance structures, and; (3) how trade occurs – how the transactions on the market take place. These rules are expressed in legislation as well as in the market actors’ understandings and practices.

Without clear property rights, it is impossible to have a market because who owns what is not known and, therefore, who is entitled to trade with the product in question. In other words, property rights are rules that define who is entitled to the profit from the sale of the goods. However, property rights can assume many different legal forms, for example, related to the different types of companies (private/family owned, partnerships and limited liability companies). What ownership rights do is they define the relationships between the owners and everyone else, thereby defining the power relationship between the parties on the market.

Control or governance structures encompass two aspects: society’s general rules regarding how competition should take place and the rules for how companies can be organised, i.e. which types of companies are allowed. These are the ‘rules of the game’ that determine how the market works. This is either stated formally in law or informally through institutionalised practices. The Competition Act, for example, aims to promote effective societal resource utilisation through effective competition for the benefit of businesses and consumers. Therefore, the law prohibits, for example, certain types of anti-competitive agreements. With regard to informal institutionalised practices, these primarily concern advice from professional organisations to market actors about how to best exploit the competition rules or how best to organise themselves in relation to their competitors.

Trade rules specify the conditions for how trade on the market - transactions - can take place. There are many different types of rules that focus on the health and safety of products, transport, insurance, contractual compliance, etc., all of which seek to stabilise the market and ensure that all companies on the market are subject to the same conditions. If trade is international, trade agreements between countries are particularly important.

In addition to these rules, the market actors’ implicit understanding of how the market should function also plays an important role. This understanding evolves over time, especially with regard to the relationship between existing companies and new companies entering the market. The existing companies on the market do not want additional competitors and, therefore, attempt to establish different types of barriers (for example, in the form of production standards), which may block the entry of new companies onto the market. The new companies will be able to challenge market stability if they succeed in gaining a foothold on the market.

Even though these four factors contribute to creating the conditions on the market, i.e. property rights, and stabilising them by specifying the ‘rules of the game’ as to how the market should function (with the aid of the competition rules) and how the transactions should take place (for example, trade agreements), the conditions are constantly being challenged. The existing companies on the market, new companies wishing to enter the market, and consumers are all interested in influencing these four conditions and there is, therefore, a continual political struggle to change them. For this reason, the market is not something that is just there. It is the result of market actors’ struggle to orchestrate, organise and design the market conditions so that they benefit themselves as much as possible. In other words, the market conditions are not a given as they could be changed if there was sufficient political support for it. Markets are created.

What creates the dynamics of the market is the competition between the sellers (companies) to ensure the buyers’ favour so they come back and remain good customers. Competition is considered to be the solution at the moment as more and more social functions are being exposed to competition, for example, the liberalisation of the electricity market or the privatisation of water supply. The reason for this is the strong impression that competition between private suppliers will ensure that society’s scarce resources are used most effectively. However, even according to mainstream economic theory, this only applies to perfect competition where the market is open to all (no barriers to the entry of new businesses), the companies are selling identical products, there are many companies present, and none of them can control the market price, while buyers have complete information about the products so that they can choose the best. However, this is far from the world of reality. Nevertheless, the idea that ‘market forces’ will ensure the most efficient utilisation of resources is widespread. Adherents to such an idea consider market forces to be natural and not something that are created by political processes.

The problem of side-effects and third parties

Susse Georg & Inge Røpke

Production and consumption involve both the use of resources and the emission of waste materials, which may cause two kinds of problems: First, resources can be overexploited and secondly, the waste materials from the process can have adverse effects. Neither of these can be said to be the aim of the process, so they must be defined as unintentional side-effects, which often affect people who derive no benefit from the production and consumption process that has caused the problems. In this case, the side-effects are said to affect third parties, which refer to people and not damage to animals or plants unless the damage is important to humans (the perspective is, thus, anthropocentric, see the theme on view on nature and ethics).

Pollution problems are often side-effects that affect third parties. The classic example is of a company that emits waste into lakes or streams, which damages fish stocks and, thus, fishermen's opportunities to catch fish. The same applies, of course, to the discharge of wastewater in towns and the leaching of nutrients from agricultural fertilisers, just as pollution affects interests other than fishing, for example, people’s opportunities for bathing. As detailed in Engberg’s book, Danish environmental history is rich in conflicts concerning the pollution of watercourses, and this continues today.

Right up until today, such conflicts have primarily been regulated through legislation involving bans and orders, often after a lot of discussion back and forth. Legislation prohibits various activities, for example, the use certain toxic substances in production, and the law demands that companies perform certain tasks in a prescribed manner. There is also extensive regulation of the products, so that users do not receive shocks from electrical items or become sick from eating food products, and so houses do not collapse. This removes the temptation for producers to make things as cheaply as possible regardless of any potential adverse side-effects for third parties.

Since the 1980s, it has become increasingly common to use other tools to regulate the conflicts, especially economic instruments. Economists, in particular, have argued that sometimes it is better to charge a tax, for example, on emissions of harmful substances instead of setting rules about how much pollution is allowed to be emitted. This is inappropriate, of course, if it concerns a substance that must be completely avoided, but if quantities need to be reduced, a tax can be useful. Firstly, it may be cheaper for society as a whole because the tax stimulates companies to reduce their emissions if it is relatively easy for them to do so, while emissions can continue in those companies for whom it is difficult to implement reductions – for them it is cheaper to pay the tax. Secondly, the tax provides an incentive for technical development, which in the longer term can reduce emissions in a more efficient way. Finally, the tax can raise funds for the treasury, which can, for example, use the money to solve some of the problems caused by the side effects.

In mainstream economics, side-effects are called externalities or external effects because they are external to the factors that are included in the decision-maker’s considerations. For example, a company is interested in the revenue and costs it has to include in its accounts, not the effects that affect others. Concerning the environment, the external effects are often negative, although they may also be positive. The classic example is bee-keeping, where it is not only the owner of the hives that benefits from the pollination of flowers. In mainstream economics, use of the term externality is often associated with the idea that, in principle, it is possible to calculate the economic value of the externality and that the introduction of a tax of the right size will ensure an ‘optimal’ result. In ecological economics, such an idea does not make sense because market prices are not considered to be a valid expression of what something is worth (see the section on value and prices in the theme on political decisions). However, ecological economists agree that in some contexts using charges as a means of control is useful, although their level must be set based on considerations other than the idea of optimality.

Economic instruments also include quotas that can be traded (such as the EU’s system of CO2 quotas and the Danish fishing quota system), and subsidy schemes to encourage, for example, the development of cleaner technologies. They may also take the form of payments to farmers or forest owners to run their businesses in an environmentally-friendly manner. This form of support is called payment for ecosystem services (PES). In addition to the economic instruments, there are a number of other tools such as the eco-labelling of products, environmental certification for companies, voluntary agreements with industry and many others (a little more can be found in the section on institutions in the theme on theoretical glasses).

Types of good and the overexploitation of resources

Up to now we have focused especially on pollution problems, but the exploitation of resources can be seen in the same perspective because it may also give rise to side-effects that impact third parties. For example, when rainforest is cut down, it affects many more than those who benefit from the felled trees or the cleared land. In the short term, those who used to use the forest for their livelihoods through harvesting fruit, rubber and engaging in other activities will be affected, while in the longer term, the climate will deteriorate, thereby affecting everyone. However, side-effects connected with the use of natural resources are often discussed in a supplementary perspective, which highlights some particular difficulties regarding regulation.

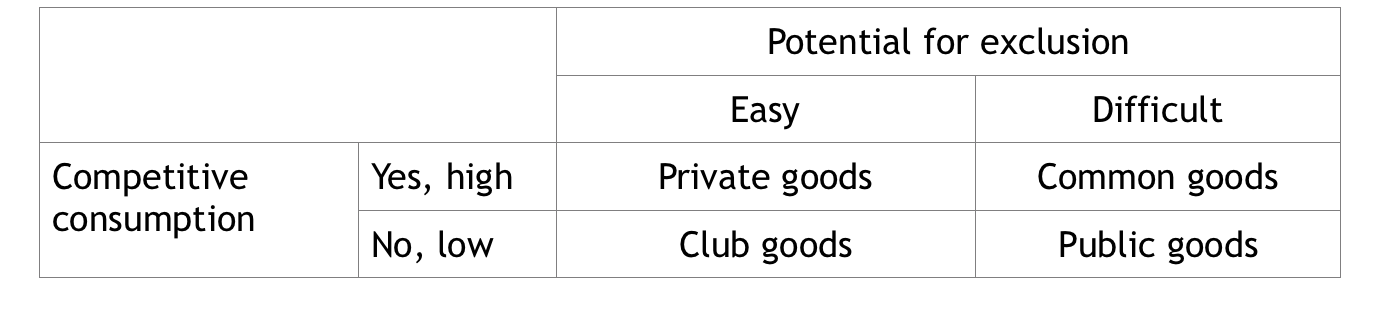

The perspective is based on a classification of goods into two dimensions. One dimension is concerned with whether an individual’s consumption of a good reduces what is available to others. If so, it is called competitive or rival consumption. A classic example is a piece of bread - if you eat a piece of bread, nobody else can eat it (unless the bread is shared). A classic example of non-rival consumption is the consumption of television signals, such as when we watch television - a household’s television consumption does not limit the ability of other households to watch television.

The second dimension concerns whether it is easy or difficult to exclude others from using the good. For example, if a person does not want to pay for a good, is it practically possible to exclude the person from using it? Goods that are sold in stores are protected by surveillance cameras and by law that punishes anyone who steals them. However, in other cases, it is hard to exclude people from using a good because it can not be fenced or protected in some other way. For example, it is difficult to monitor a forest to make sure that people do not help themselves to logs, even though it is not allowed. It is particularly difficult to prevent people from using a good that is not divisible, such as clean air, or the signals from a lighthouse.

Based on these two dimensions, goods can be classified into four different types, as presented below:

- If it is easy to exclude others from consuming the good, while at the same time an individual’s consumption reduces the consumption of others, it is called a private good. Typical examples are bottled water, food, clothing and many other types of good. If you drink the water or eat the food or wear the clothes, nobody else can do the same with these products.

- In cases where consumption of a good limits other people’s consumption of it only to a limited extent or not at all, it is called a club good (also called ticket goods). A classic example of this is when television signals are put together in ‘packages’ on cable television, which one has to pay for to watch. Those who do not pay, can not watch the programmes that are included in the package, but when you watch a programme in the package, your usage will not reduce the ability of other paying consumers to also view the programmes in that package.

- If it is difficult to exclude people from consuming a good and there is no competitive consumption, it is called a public good. Typical examples are the prevention of crime or national defence, which provide protection to everyone within a specific area. As the goods can not be divided and sold to those who want to pay, they are usually secured through tax payments from the population of the relevant areas. In this way, governments seek to avoid situations where individuals can free-ride, i.e. attempt to avoid paying even though they benefit from the protection that others in the area pay for.

- In contrast, if consumption is competitive, and it is also difficult to exclude people from consuming the good, it is called a common good (or common pool resources). Fish stocks in the sea and groundwater resources exhibit these characteristics. It is difficult to prevent people from consuming such resources, and when too many people use them, problems connected with overuse may occur.

In practice, the classification is not as clear-cut as described above. There are many border cases between the different types, while the position of a good may change over time. For example, technological change may influence the potential for excluding people from using a good, such as GPS, which has made it easier to control who is catching fish in the oceans. The degree of scarcity also changes over time, so that natural goods, such as pure water, can change from being public goods with low rivalry in consumption to being common goods.

Schematic categorisation of types of good.

With regards to the environment, common goods and public goods give rise to particular problems. When there is a lot of pressure on resources, common goods can easily become overexploied. For example, overfishing can lead to the gradual depletion of the fish stock and, thus, limit fishing in the future. In order to solve such overuse problems, rules about who can fish, how much and when must be implemented. As a rule, the smaller the scale and the fewer the parties involved, the easier it is to establish these rules. In relation to the overexploitation of fish stocks, it is possible to control who has access (the right) to fish locally (in lakes, rivers or coastal waters) by issuing fishing permits. In the case of commercial fishing, where fishing takes place in certain marine areas, the countries that have fishing interests in these areas negotiate with each other about the size of the fishing quotas. During these negotiations, the countries decide who is permitted to fish in the area concerned, and how much fish they are allowed to take.

The climate problem is an example of how difficult it can be to share the burden when it comes to providing a public good, in this case a climate where the temperature rise is limited to one-and-a-half or two degrees. Our local consumption of fossil fuels and the associated CO2 emissions contribute to the greenhouse effect and change of the global climate system. The consequences of this are not only felt now (for example, extreme weather conditions are occurring more frequently), but are also expected to affect the living conditions of future generations. Reducing CO2 emissions would be beneficial for everyone, but it has proved very difficult to reach agreement on binding agreements to do so. This is due to several factors: the fact that many countries are heavily dependent on fossil fuels, differences in countries’ development - for example, a fear among developing countries that their opportunities for improving living standards will be limited - and conflicting interests within each country with regard to the phasing out of fossil energy sources. If we do not get CO2 emissions (and other greenhouse gases) under control, we expect a global temperature increase of as much as six degrees. According to the famous climate scientist, James Hansen, this would lead to ‘a completely different planet’.

Next: Property rights and commons

Property rights and commons

Susse Georg & Inge Røpke

The classification of the different types of goods is based on purely practical assessments of their characteristics: Is it practically possible to exclude people from using them, for example, if they do not want to or can not pay? Will an individual’s consumption of a good reduce the ability of others to use it? Therefore, the types of good are not defined according to how property rights are organised. It is difficult to make some goods private property if it is not possible to exclude others from using them when they do not pay, but for other goods, there are many opportunities for organising property rights. A service such as hospital treatment is a private good because users can be excluded and because it is scarce. However, there are big differences in how different countries organise the supply of this good: while hospitals are mainly public in Denmark, they are private in the United States. A central discussion in the field of the environment is focused on how property rights for natural resources can best be organised in order to avoid overexploitation. Much of the debate has been based on the concept of commons.

Most are probably familiar with Fælledparken (the common park) as the place in Copenhagen where many celebrate 1st May. This very popular park was originally a common grazing area for cattle. From sometime in the 1400s to the early 1700s, the local residents had common property rights to the area. Each farmer could graze a certain number of cattle on the grass according to a carefully agreed system. Therefore, free access to unrestricted use of the common was not the case. Rather, access was organised in the form of a kind of quota system. From the early 1700s and the next two hundred years, the common was used for military purposes until the area was taken over by the City of Copenhagen and transformed into a public park (1908-12).

However, commons were not solely a phenomenon of Copenhagen, they also existed in many villages around the country. Their use was regulated by common law - rules which had gradually been developed in the village communities in order to safeguard against the overexploitation of the areas. The introduction of the agricultural reforms (in the mid-18th century) marked the start of the decline of the commons, while each landowner’s land within the village was separated.

Such village commons have long since disappeared in Denmark. However, the phenomenon still attracts much attention, partly because many natural resources are common resources, but also because new forms of commons are emerging as a result of societal development.

One of the most well-known narratives about commons is that they are synonymous with tragedies; a connection that was established in the article ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, which was published in the most prestigious journal Science in 1968. The article concerns a common grazing area that is accessible to all. According to the author, Garrett Hardin, the tragedy occurs because the most rational action for each individual farmer is to exploit the grazing area as much as possible (to graze his animals). When everyone acts in this way "Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all" (Hardin, p. 1244). There is an implicit assumption in Hardin’s argument that the tragedy could be avoided by introducing private property rights. Only in this way would farmers have an incentive to take care of (their respective part of) the grazing area.

Many years passed before this narrative was criticised. The Nobel Prize winner, Elinor Ostrom, and her research group have documented how communities in many places around the world have actually developed different ways of managing their shared use of grazing areas and other forms of common resources, such as forests, fishing grounds and groundwater reservoirs. Against this background, they have been able to highlight the hidden assumptions in Hardin’s story. Furthermore, they have pointed out that Hardin’s story does not concern commons, but instead grazing in cases where there is free access to the limited resource (open access and, thereby, no social control). Therefore, he had overlooked the possibility that people in fact collaborate to find solutions to their common challenges.

Hardin’s article compares two types of property rights system: private, individual property rights, which was Hardin’s solution to avoiding the overuse of a scarce resource, and open access, which means that no one has ownership (or if someone has, it is not enforced). The latter was the tragic phenomenon he actually described. However, Ostrom has identified two additional systems of property rights (some call them property regimes): group property rights, which is developed in a group to regulate use and prevent others from exploiting the resource, and state property, which is when the state has the right to exploit the resource. One of the results of her research is that you can not say, in general, that one property rights system is better than another at regulating resource consumption as this must be determined in specific circumstances.

Based on her studies, Ostrom has established eight principles for managing common resources:

- The group that wants access to shared resources must be clearly defined - when people know each other, they are more likely to trust each other.

- The ‘rules’ for people’s use of the shared resources must address local needs and conditions, otherwise there will be greater risk that people will not comply with the common rules.

- For the same reason, those who are affected by the rules must also have the opportunity to influence their development. There must be a democratic process.

- The local society’s self-regulatory measures must be respected by external authorities.

- A system that community members can use to monitor the behaviour of group members must be developed.

- Sanctions for those who violate the community’s rules must be graduated.

- Provide accessible and inexpensive forms of conflict resolution.

- The responsibility for regulating resource consumption must be built from below.

This does not mean that a local community will necessarily develop the rules or mechanisms that can manage the use of a common resource because many problems can arise along the way. For example, some may not want to comply, some may want to decide too much (be more powerful than the others), or other types of conflict may emerge.

Nevertheless, today, the concept of the commons serves as a model for how to find new ways of managing our resources. For example, many consider urban space as a form of commons - it is difficult (and/or costly) to exclude others from using it, while one person’s consumption of it may well reduce the potential for others to enjoy the same urban space if the person, for example, vandalises the area. Kitchen gardens are something that all passers-by can enjoy, but they are difficult to protect against vandalism unless it is possible to develop a norm in the local area that such behaviour is unacceptable and somehow apply sanctions on those who destroy the gardens. For many, the question of (re) introducing commons in cities concerns residents’ democratic right to influence the development of their neighbourhood.

Viewed from this perspective, commons encompass more than just biophysical common resources (see the examples of urban space or kitchen gardens above). In these examples, the commons are associated with fundamental ideas about what constitutes good urban life - what some call ‘liveability’ – and an ideal of getting closer to nature. At the same time, commons are also involving - people become engaged in ensuring the development of their local area, which can influence people’s identity and their sense of belonging. Commons are socio-economic, biophysical systems or communities.

Next: Markets and environmental regulation

Specific environmental problems

Susse Georg & Inge Røpke

Specific environmental problems emerge in many different ways. A classic problem is that an important resource becomes depleted. As a Danish example, in his doctoral thesis (Den danske revolution 1500-1800. En økohistorisk tolkning, 1991), the historian, Thorkild Kjærgaard, discusses how Denmark, in the first half of the 18th century, ran into an ecological crisis, especially because the forests were disappearing. While 20-25% of the country was covered in forest around 1600, this percentage had fallen to only 8-10% of the country around 1750 (p. 23). As timber was the most important raw material and source of energy, the decline was a problem in itself, but it also led to other related problems such as worsening sandy drifts. Many interrelated factors contributed to the ecological recovery, while also creating the basis for more recent environmental problems; not least those that are linked to the increased use of fossil fuels.

Other classic problems are connected to societal changes such as rapid urbanisation with which infrastructure planning can not keep up, thereby leading to new side effects. The book Det heles vel. Forureningsbekæmpelsen i Danmark fra loven om sundhedsvedtægterne i 1850’erne til miljøloven 1974 (1999) by the historian, Jens Engberg, talks about the horrible living conditions in Copenhagen in the mid-1800s, when the population grew from approximately 100,000 inhabitants in 1801 to approximately 155,000 in 1860 (p. 23), waste of all kinds piled up and mortality was very high. The book also highlights the many new problems that arose as a result of early industrialisation during the same period and the problems that arose following the introduction of new pesticides in agriculture in the 1930s. Establishing regulations of environmental problems takes a long time, and because new problems are constantly emerging, we are still not finished.

Acknowledging environmental problems

The first step in dealing with a problem is acknowledging that it is a problem. Throughout history, a lot of time has passed from when the first critical voices have begun to highlight something as being a problem to the first attempt is made to do something about it. For example, it took a long time before the first danger signs led to a recognition of the problems connected with lead in petrol, the use of asbestos in buildings, the collapse of fish stocks, and the consequences of pesticides for men’s fertility (a large number of case studies are gathered in two reports from the European Environment Agency titled ‘Late Lessons from Early Warnings’, 2001, 2013).

Some problems may be difficult to discern because the harmful effects of a particular activity may not be apparent until much later or much further away, and because the causal relationships can be difficult to establish. However, at other times there may be solid evidence, which does not lead to action because it would cross powerful special interests, because it ‘only’ affects weak groups in society, or because the majority of society prioritises other issues. The opposition to doing something can be reflected in counter-documentation, although such a strategy is obviously difficult in situations where the connections are obvious. Therefore, highly visible problems can be easier to address, especially when they affect a number of groups in society at the same time.

Conflicts of interest and balancing

In a Danish context, the long road to modern environmental regulation is, as previously mentioned, described in Engberg’s book. The book illustrates that many environmental problems, such as waste management, water supply, sewage, the use of toxins in agriculture and the pollution of various industries - have a long history, and that efforts to regulate have often encountered great resistance. One of the central problems is that environmental improvements often require interfering with property rights, i.e. the owner’s right to do what they want with their property. When doctors attempted to improve people’s health in Copenhagen in the 1850s and reduce the risk of epidemics, they saw no other way: "The free use of houses and grounds should be limited to such an extent that the individual’s capriciousness or selfishness can not interfere with the common good"(Engberg, p. 47). At the time, this view came into conflict, just as it does today, with the traditional legal understanding of legal rights, which focuses on protecting owners from government intervention. Therefore, it has been an important aspect in the subsequent development of the field of environmental law to argue for another concept of legal rights that focuses on protecting the interests that may be affected by the owners’ use of their property.

In addition to the countless examples of special interests, there have also been many examples in history of the more general dilemma that society faces; the fact that pollution control is not free. For example, in 1969, while preparing comprehensive legislation on pollution control, the Social Democrat, Erling Olsen, wrote: “What would we prefer? More clothes? Better food? Better and more furniture? More and longer holidays? Larger cars? Colour TV? Or fresh air, clean water and less noise in everyday life?” (Engberg, p. 378). When you read about the debate in Denmark at that time, it is easy to draw parallels with the current debate in China, where urgent environmental problems face aspirations for better living standards. In Denmark, environmental problems and consumption wishes have both changed, but the problem is still present.

Next: The problem of side-effects and third parties

Introduction: Control and regulation

In the themes on energy, metabolism and growth, the focus is on environmental problems in an overall perspective: changing the energy basis in a long-term perspective, growth of the economy as a metabolic organism and the ethical problems that are associated with the challenges. The themes also discuss how researchers have attempted to highlight the biophysical growth of the economy and the planetary boundaries we have either exceeded or are about to exceed. However, when it comes to environmental policy in practice, more delimited problems are often in focus. One can say that the overall growth of the metabolism is reflected in a wide range of specific environmental problems which have emerged over the years and demand attention. In this theme, we look at different methods of controlling and regulating these problems.

Next: Specific environmental problems