Tools of persuasion

Emil Urhammer

In this section, we attempt to describe a feature of the economic measures and models that has not been the subject to much research - not in mainstream economics or ecological economics. However, they have been addressed in the so-called ‘science and technology studies’, which assert that economic measures and models are not passive reflections of a completed economic reality, but that instead they help to create and produce economic reality in certain ways. In this way, economic measures and models can be viewed as tools of political persuasion that have a major influence on social conditions. Examples of this are GDP, which helps define what is good and desirable in terms of societal development; cost-benefit analysis, which influences important policy decisions, and the Ministry of Finance’s macroeconomic models, which are used to guide the government’s economic policy. These tools are characterised by a particular view of the economy, where markets and prices are the dominant factors, while ecosystems and ethics do not really play a role. The struggle over economic policy can, thus, also be seen as a battle between different tools of persuasion, where mainstream economics emphasises GDP and cost-benefit analysis, while other economic schools apply biophysical indicators and emphasise distribution between different groups in society as crucial.

Societal measurement tools: management and performativity

Jens Stissing Jensen

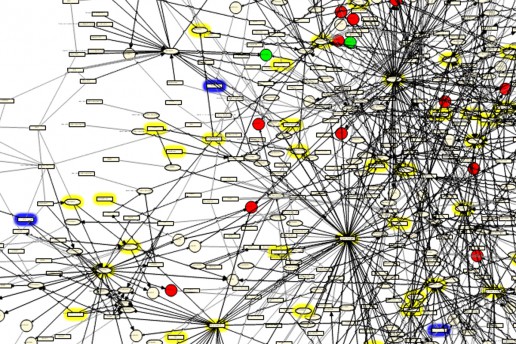

Societal development largely depends on managing processes and systems such as ‘the economy’, ‘the food production system’ or ‘the transport system’. However, these systems are phenomena that can not be observed or sensed in the same way as a house or an animal. Nevertheless, societal governance requires that such systems and processes are made visible. To this end, a large number of ‘measurement tools’, which attempt to determine the state of health and the development of these societal processes and systems, have been developed over time. Such measurement tools constitute a kind of expanded sensing device that politicians, planners and officials use to assess the necessity and effect of new policies and strategies. For example, the economic reality is presented as a controllable political and administrative entity by way of continuous measurements of GDP, unemployment and inflation.

However, measurement instruments can never give a full representation of the social reality because they only measure selected and delimited parameters. Therefore, societal governance may fail if the parameters measured by the instruments are not appropriately defined. For example, measuring inflation is typically used to assess the extent to which the economy is approaching overheating. However, measuring inflation was unable to identify the overheating of the economy that led to the financial crisis in 2008. This is, amongst others, due to the fact that inflation is only measured by price increases for consumer goods. The measurements, therefore, did not identify the explosive increase in house prices, shares and financial products as evidence of speculative economic overheating. Therefore, the economic overheating was not captured by the measurement instruments that are traditionally used to identify this phenomenon. Consequently, a challenge for societal governance is to continually adjust the measurement instruments in such a way that they provide an adequate representation of the social reality.

In addition to creating controllability, measurement instruments also have a so-called performative function, which means that they actively help shape the way in which planners and politicians perceive societal issues. This is because measurement instruments can be set up so that they make the social reality appear in many different ways. For example, the established economic measurement instruments primarily determine whether the economy balances in financial terms: Do the public finances balance? How big is the private debt? Are investments in production machinery increasing? As these financial balances are made visible through measurements, the balances become prominent issues in political reality. Thus, the measurement instruments exclude a number of important factors by, for example, not including any measures for the biophysical development of the economy.

Measurement instruments can also be used ‘performatively’, i.e. to redefine which phenomena and relationships are made visible or invisible, and thus what problems the political system is able to spot. For example, measurment instruments have played a performative role in the planning of cycling infrastructure in Copenhagen over the last 20 years. Until the mid-1990s, planning was primarily based on measuring the number of cycling accidents, which meant that most of the planning was directed at reducing bicycle accidents. Since then, a new measurement instrument has been developed; the so-called bicycle account, which also recorded cyclists’ experiences in terms of safety, comfort and convenience. Due to the influence of this visibility, planning began to focus on creating good and attractive cycling experiences. Recently, the City of Copenhagen has developed another measurement instrument that focuses on the health-promoting effects of cycling. This visibility has been central to the establishment of regional super cycle paths. The development of new measurement instruments has, thus, contributed to ‘redefine' cycling so that it is no longer defined by accidents, but instead is linked with good experiences and the promotion of health.

Societal governance and development are, thus, closely linked to the use of measurement tools. Measurement tools are necessary to describe and identify the state of health and development of societal processes and systems, which can not be done directly through our sensory apparatus. Societal measurement tools function as a sort of expanded sensory apparatus, which can be used to influence which issues attract the attention of the political system by making certain objects and relationships visible, while concealing others.

Systems thinking

Emil Urhammer

Among ecological economists, it is very common to use the word system. According to the system theorist, Donella Meadows, a system consists of a number of connected and interacting elements that are organised in such a way that they achieve something specific. In some cases, systems are organised with a particular aim in mind from the beginning, while in others, the organisation just gradually emerges. As a result of its internal organisation, a system can maintain its existence by means of a number of mechanisms in an interaction between its various parts.

According to Meadows, most system theorists agree on the following three overall features of systems: (1) The behaviour of systems is determined by their internal structure. External influences can change the functioning of a system, but the different modes of operation of the system are hidden as potential in the system itself. (2) It is very difficult to define a system. In most cases, no real system border will exist. Instead, the boundary between the system and the outside world is defined by the analysis that is conducted. (3) Systems can often be seen as systems within larger systems. In this way, systems are often characterised by a hierarchy with one system actually consisting of a number of smaller subsystems which are embedded in and function as elements in the larger system.

From the above very broad description, it is apparent that systems can be many different things. For example, a small forest lake with fish and aquatic plants can be seen as an example of a system - an ecosystem where different animal and plant species live and interact with each other. But systems are not only found in nature. For example, a society’s transport network can also be seen as a system - the transport system - and a society’s economy is also perceived by many as a system. In these examples it is possible to identify a hierarchical organisation. The forest lake is a subsystem of the entire forest ecosystem, train transport is a subsystem of the whole transport system, while the transport system can be seen as a subsystem of the overall economic system.

Through the interaction between different elements, a system can achieve a certain state that can change over time. For example, in the case of the forest lake, a particular species can ensure that the water in the lake is clear by eating algae, which would otherwise make the water cloudy. However, if the the system is pushed from the outside, its state can change. Perhaps nutrients from a farmer’s field leach into the lake so the algae obtain plenty of food, or perhaps the species that keeps the algae population down disappears because of fishing. Both can help change the balance in the lake. Such changes are often very difficult to predict because they often rely on complex interactions between the internal elements of the system, which we do not understand or are even aware of.

As described above, you can apply systems glasses in the study of many different things, and interactions between species in nature, modes of transport and economic entities can all be seen as system interactions with different feedback mechanisms. Thus, it is possible to apply systems thinking across the gap between nature, society and the economy, and it is, as previously mentioned, very difficult to distinguish the different systems from each other. The small forest lake is connected to the economy because the farmer’s economic activities influence its state, while the economy is connected to the transport system because goods and people need to be transported in order for the economy to function. Therefore, one of the major challenges in systems thinking is defining the system you want to investigate. However, this can be done by, for example, simplifying and omitting various connections to other systems.

In systems thinking and, in particular, the question of sustainability, resilience is an important concept, which concerns the ability of a system to maintain a certain state despite external influences. If we think about the forest lake’s ability to keep the water clear, one can say that the resilience is low if the farmer can only apply very small amounts of nutrients before the water becomes cloudy. In the same way, one can say that the resilience is high if it is possible to catch a very large amount of fish which keep the algae level down before the lake becomes cloudy. In the latter case, the high resilience of the system may be due to the existence of other species of fish in the lake, which also help keep the overall volume of algae down. When a species is under pressure, other species can take over and perform the same task. This capacity is important for resilience and is one of the reasons why biodiversity is emphasised as being so important for the survival of ecosystems.

System theorists often also talk about so-called tipping points, which is the point where a system goes from one state to another. If we consider the forest lake again, the tipping point is precisely when the amount of nutrients entering the lake exceeds the ability of the system to keep the water clear; the result being that the water becomes cloudy. When looking at the economy, for example, the tipping point may be when a housing bubble bursts and the housing market collapses with plummeting house prices, bankruptcies and foreclosures.

Institutions

Susse Georg

We often talk about different kinds of institutions, such as children’s institutions, educational institutions, prison institutions or more generally, public institutions. At the same time, many also use the term to refer to important organisations, such as the UN, which is an international political institution, or the World Bank, which is a major international financial institution. According to these applications, an institution may either be a physical place or an organisation that performs certain tasks. However, institution can also mean something completely different, i.e. social order or a social pattern, which is maintained through human interactions. Based on this definition, institutions regulate human behaviour and are, therefore, crucial for a sustainable transition of social development.

The word institution comes from the Latin word instituere, which means ‘to set up or establish’. Although institutions are often taken for granted, they are not just there. They are socially created. Consider many of our everyday actions such as eating dinner together. It is something people have always done, and it is something that is done in many different ways. However, what is the same is that having dinner together is a learned act. In most families, it is the adults who decide when and where the family should eat (for example, at the dining table or in front of the television) and the children just comply. While adults are to some extent conscious of the habits they establish, children (especially younger ones) are unaware of them. For them, it is just the way things are done. When the children move away from home and establish their own families, it is quite likely that they will continue many of the same habits that they grew up with in their families. Over the years, a gradual institutionalisation of the way people eat dinner has occurred. According to the sociologists, Berger and Luckmann, this institutionalisation process consists of three steps: firstly, the habits must be established. In relation to the example above, this occurs when adults develop their eating habits (probably before they get children) and mutually acknowledge them. Berger and Luckmann refer to this mutual recognition as ‘typification’. When the children arrive, they experience the habits as facts - as an external force which they have to comply with. The habit that was created by the parents becomes objective reality for the children. This step is referred to as ‘objectivation’. The final step 'internalisation', is when the children reproduce ‘what they learned at home’.

There are many other types of institution than those that regulate the way we eat our dinner. They are established, maintained and developed in the situations where people interact repeatedly. Institutions are essential and allow us to coordinate and control things. According to the sociologist, Richard Scott, institutions consist of cognitive, normative and regulatory structures that give social behaviour stability and meaning.

The cognitive structures relate to the conditions that can affect our thinking habits and understandings. Language is particularly important in this respect. Language is a system of signs that enables people to express themselves and it is, therefore, important for the above-mentioned objectivation of everyday reality. More generally, symbols - whether they be words, signs or gestures - all help us to understand what is happening around us. They influence how we make sense of things and contribute to establishing what some call our ‘cognitive map’ - the framework for understanding through which we make sense of things. The creation of meaning takes place individually as well as collectively - it takes place in a concrete connection and is, therefore, also influenced by the cultural context. In every context there are some fundamental rules that determine how things, relationships and processes are categorised, i.e. how the above-mentioned symbols are arranged. If we take the issue of climate change as an example, there are major differences in people’s understanding of the seriousness of the situation. While the vast majority of people now consider climate change to be man-made, there are climate sceptics who believe that this is not the case. According to their world view, climate change is something that has always been around. The many scientific reports that document the seriousness of the situation in various ways have not influenced their perception of what is ‘real’.

The normative structures encompass different types of rules for how to behave. In other words, they specify what is correct or appropriate, while at the same time they involve assessments of whether people are following the norm. There is an element of coercion because people are expected to comply with the norms. Norms influence many things, for example, what is considered the appropriate way of treating the elderly or foreigners, what behaviour is acceptable in the workplace or the appropriate use of mobile phones. If you do not comply with the norms, you may face different types of sanction, which may range from a raised eyebrow and a shake of the head to verbal reprimands. Bullying can be regarded as a particularly malicious form of sanctioning that implies that you do not fit in with some of your classmates’ norms that dictate the right way to be.

What all norms have in common is that they are based on some underlying values as to what is desirable. This becomes a ‘standard’ against which people’s behaviour is judged. Norms express certain expectations regarding our interpersonal relationships - they indicate the correct way to do things. In addition, it can be said that norms define what the appropriate - or legitimate - means are for achieving a specific goal. Legitimacy is something most organisations strive for as it represents their ‘license to operate’. In the last 40 years of development in industry, norms for a company’s social responsibility, known as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), have gradually developed, strongly encouraged by environmental, work environment and labour market legislation (see below). However, what CSR more specifically involves is something that many consultancy companies like to advise industrial companies about. Consultancy companies, among other things, earn their keep by formulating rules, guidelines and voluntary standards that define what constitutes responsible corporate operations. The spread of such rules and standards helps to define what is considered legitimate business conduct. In order for a company to maintain its legitimacy, it must be able to justify its choices/actions. For example, the VW Group has had a lot of difficulty with this in the aftermath of the repeated scandals in 2016 when it became known that their cars pollute much more than the company had stated.

The regulatory structures include legislation, rules, contracts and other forms of formal agreements as well as the necessary monitoring and sanction systems that are required to ensure compliance. This requires an authority with the necessary capacity to: (1) establish the rules; (2) investigate and monitor to ensure others are complying with the rules, and; (3) impose sanctions if necessary either in the form of a penalty or reward with a view to influencing the actions of others. What the regulatory structures have in common is a statement of what the involved parties may and may not do, and that there is one or another form of penalty if this is not followed.

Development in the environmental field serves as an interesting example of how regulatory, normative and cognitive structures are intertwined. The Environmental Protection Act was introduced to help ensure that societal development is sustainable by making companies reduce their pollution of the air, water, soil and underground. Companies are thus subject to a number of rules that they must adhere to. If not, they can be reported to the police and may receive a fine. During the 40-year history of the Environmental Protection Act, two significant changes have been made to the goals and measures of the law: From focusing on environmental protection, the goal has been changed to include the prevention of problems. At the same time, the widespread measures (approval of the companies’ production and emissions) have been supplemented by an increased use of voluntary environmental management standards (self-regulation) to promote the companies’ environmental work.

This development must be seen in the light of the great political interest in simplifying the legislation and streamlining the public sector, which is linked to the introduction of New Public Management in the public sector in the mid-80s. The authorities’ limited resources to control companies was one of the factors that helped to legitimise an increased use of self-regulation. At the same time, many believed that in this way, they could achieve better (environmental) results because the companies would be more motivated and would find it easier to comply with conditions, the arrangement of which they had been involved in. The three types of institutions - cognitive, normative and regulatory - support each other: Environmental standards are normative regulations that stipulate how companies’ environmental efforts should be organised. The introduction of these works together with ideas about what best encourages companies in terms of their environmental work, and with ideas about the need to streamline the public sector. Together, this justifies the use of normative instruments in addition to judicial regulation.

Institutions are important sources of power: The cognitive structures influence our framework of understanding; our perceptions of what is real and important. Our interpretation of what is happening (or has happened) around us depends on our knowledge and the models of understanding we apply. And here the normative structures, such as upbringing, schooling, educational choices, etc., play a role and shape our views on how to behave and how development should take place. The cognitive and normative structures thus work together in creating our understanding and expectations and, thus, have ‘power to define’ to a certain extent. The regulatory structures are perhaps more tangible as they are laid down in laws and contracts. By stipulating who is entitled to what, it is possible to ensure ‘law and order’ and protect the interests of the different parties. However, it is by no means certain that all interests are weighted equally. As a result, ‘positional power’ may be established, where some have more right or more rights than others. Such bastions of power are far from secure or stable - they can be and are challenged by people who think and act in a different way to that which is prescribed by the institutions.

Because institutions are socially constructed, they are also changeable. Things can be different. The introduction of new technology is often the reason why institutions change. Just think about the development of the Internet and the resulting opportunities to acquire information and keep in touch with people over great distances. At the same time, it has meant changes in our perceptions and norms. Ten years ago, reading a newspaper during a class was perhaps not unthinkable, but it was at least frowned upon. However, today, teachers have to deal with students’ use of Facebook and other social media during teaching. Similarly, a few years ago, opening and reading post while in a meeting at work was unthinkable. You just did not do it. But today, checking email while in a meeting has almost become normal. This erosion of what is considered acceptable behaviour illustrates that institutions can be changed (relatively) quickly.

Ensuring a sustainable transition demands that changes are made to many institutions, from our perception of what constitutes human society (a metabolic organism) and what it can withstand, to our norms about how we should interact with each other and nature and to the legislation that needs to be formulated in order to promote the transformation of our energy system, etc.

Introduction: Theoretical glasses

A theory can be understood as a particular type of glasses, which make it possible to see certain things while other things disappear. The glasses are, therefore, decisive in terms of what you are able to see. While the other sections present theoretical glasses that focus on what could be called the core subject matter of ecological economics, this section contains examples of theoretical perspectives that are not specifically about the environment. Ecological economics is inspired by and draws on different understandings originally developed within other theoretical schools. This applies to both general understandings such as systems thinking, which cut across academic disciplines and more specific theories from other economic schools that differ from mainstream economic theory such as classical institutional economics.